“I have created a very complex mixing, routing system within

AudioMulch. This mixing system includes a total of 48 (and sometimes

more) different channels of FX that are all very different from each

other and all routed to each other in a special way”.

Turkish musician and composer Erdem Helvacioglu

has an international reputation for his electroacoustic music, and is

perhaps most well known for the way he combines solo guitar with live

electronics. As well as releasing critically acclaimed albums, Erdem

composes for film and theatre, and has been part of the lineup of

Turkish punk band Rashit.

Erdem is a long time user of AudioMulch, and we were keen to learn more about how he uses it.

How does AudioMulch fit into your sound design and production process?

Erdem: I can say that Audiomulch is one of the most important sound

design tools for me. I use it in every aspect of my work: film music,

electroacoustic composition and pop music production work. For pop

production, I process things like the drum tracks and vocals in

AudioMulch and export these new processed files for use in the final

mix of the song. For my film and electroacoustic work, I create more

complicated setups. These setups may involve the use of tens of

plug-ins at the same time and automation of hundreds of parameters.

Similar to my pop work, I export these sonic creations to be used

within the final mix.

How do you use AudioMulch in live performance?

I use Audiomulch with my acoustic guitar setup. This setup includes

an Ovation custom legend 1869 electric-acoustic guitar, a Sansamp

acoustic DI, a Carl Martin compressor, a Behringer FCB 1010 MIDI foot

controller, a TC Electronic Fireworx hardware multi effects processor

and a small analog mixer. The guitar signal is routed to the

compressor, the acoustic DI and then finally to one of the mixer

channels. Through the two aux sends, this signal gets routed to

AudioMulch and TC Fireworx. The outputs of AudioMulch and the Fireworx

get connected to the mixer too. This allows me to send these two

different systems to each other for more interesting sonic results. I

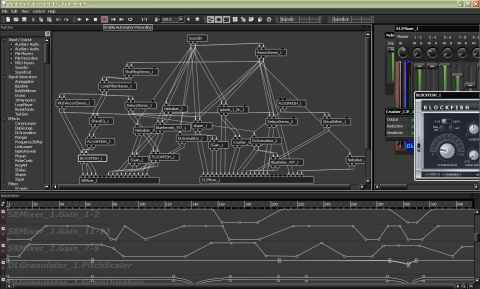

have created a very complex mixing, routing system within AudioMulch.

This mixing system includes a total of 48 (and sometimes more)

different channels of FX that are all very different from each other

and all routed to each other in a special way. These FX include the

DLGranulator, FrequencyShifter, Nebuliser, DigiGrunge and lots of VST

plug-ins. Besides this complex routing system, I also control selected

parameters in real-time either with a MIDI controller, the Metasurface,

with the mouse or as automations in the timeline.

A screenshot of Erdem’s AudioMulch patch for “Shadow My Dovetail” from his album Altered Realities.

Click for a closer look

What are your studio and live performance setups?

Besides my software setup, I have a big collection of hardware

equipment. As a composer, I definitely believe that one should have

access to both unique hardware and software gear. I have many electric

guitars, a unique handmade Togaman violguitar, many analog pedals

including the whole Moogerfooger collection, Zvex, MXR and

Electroharmonix pedals. For hardware FX units, I use the Eventide

Eclipse, TC Electronic Fireworx, Lexicon MPX100, Lexicon Vortex and

Korg Kaoss Pad. For synths and drum machines, I use the Access Virusb,

Waldorf Blofeld, Korg n5, Korg er1 and Machine Drum. I use Cubase,

Soundhack, Metasynth, Soundforge besides AudioMulch.

For my studio work, I use a combination of this equipment with the emphasis being on AudioMulch for creative sound design.

For the live acoustic guitar and electronics work, I use the setup described above.

I also have a live guitar and electronics setup that is completely

hardware-based. This setup includes my Les Paul electric guitar, a

Marshall JMP-1 pre-amp, an Eventide Eclipse, a TC Electronic Fireworx,

a Lexicon MPX100, an Eventide TimeFactor and various analog pedals.

I have a large collection of instruments including an Iranian santoor,

a Turkish bowed tanbur, an ud, a lapsteel, a mandolin, and various

percussion instruments that I record for my film work. I recently

bought a new violguitar built by Jonathan Wilson in LA. This is a

futuristic, hybrid instrument that is played by a bow. It is one of the

most inspirational instruments that I own and it is such a great tool

for creating interesting textures and film work.

Do you have any favorite VST plug-ins?

This is a hard question to answer since I use so many different VST

plug-ins and most of them are unique in their own way, but I guess I

can state that some of my favorite VST plug-ins are Delaydots Spectral

Pack, Antares’ Filter, GRM Tools, Fishphones, Izotope Spectron, PSP

plug-ins, Soundhack Spectral Shapers, AbVST and plug-ins by

Smartelectronix.

Can you describe some of the techniques you used in your albums Altered Realities (New Albion, 2006) and Wounded Breath (Aucourant, 2008)?

I used two different approaches for these two albums. Altered Realities

is an album of solo acoustic guitar and live electronics, whereas

Wounded Breath is an album of electroacoustic tape pieces.

For the Altered Realities album, I used the complex routing, mixing

setup that I described above. Many of my guitar and electronics records

are based on either long or short loops that control the main structure

of the pieces. But on Altered Realities, there is no use of loops at

all. Rather than using loops, I tried to create long textures that

change, evolve over time using many different FX parameters and complex

automation.

Listen to an excerpt from “Shadow My Dovetail” from the album Altered Realities

On Wounded Breath I used a similar system, but involving exporting

sounds for re-processing and final mixing.

The sounds I created were mostly long textures that evolve spectrally

over time. The single hits and short sounds were created and processed

within Cubase. For a single sound, I would sometimes use so many

different contraptions and automations that the CPU usage on my machine

would hit 90%! Creating the pieces on the Wounded Breath album live

would mean a hundred MacBook Pro machines running simultaneously at max

CPU! So my process was iterative: after creating the textures I would

mix a part of the piece, export that segment and process it again

within AudioMulch.

The piece “Below The Cold Ocean” on the Wounded Breath album is a very

good example of this working method. This piece also received a prize

at the prestigious Luigi Russolo Electroacoustic Music Composition

Competition.

Listen to an excerpt from “Below The Cold Ocean” from the album Wounded Breath

What are the main features of AudioMulch that you tend to use?

The main features of AudioMulch I use are parameter control and

automation, the Metasurface, the LoopPlayer, FilePlayer, FileRecorder,

DLGranulator, DigiGrunge, FrequencyShifter, Nebuliser, BubbleBlower,

and occasionally the LiveLooper for looping some of the FX returns.

Do you have any favorite contraptions or techniques?

My favorite contraption is the DLGranulator. It is a great granulator,

and I have used it for both my live electronics and electroacoustic

sonic design work.

If you had control of Ross’ development schedule, is there any feature you’d make him add to AudioMulch?

I would very much like Ross to add LFOs (low frequency oscillators),

various envelope and sequencing contraptions that can be assigned to

any parameters. In combination with the automation and the Metasurface,

this would make AudioMulch an even greater tool for sonic processing in

real-time. Also, it would be great if AudioMulch could be used as a VST

plug-in within sequencer programs such as Cubase and Protools. That way

we could have the option of using the program either as a stand-alone

application or as a VST plug-in within those sequencers. Besides these,

I also definitely need a feature where we would be able to create sub

patches. My patches are so dense; sometimes I begin to lose sight of

what is connected to where. Being able to create sub patches would

really help users like me who create dense patches with lots of

routing.

You’ve been quoted as saying:

“For me, the compositional process involves the guitar and the

electronics equally. It’s not like I have a musical idea, and then try

to find electronics to go with it. Or that I find a cool patch, and

then try to play music using it. I start with both simultaneously—much

like one might compose parts for a chamber orchestra.”

[1]

What do you mean by “simultaneously” here? Does that mean you spend

time jamming with AudioMulch (or other software) with your guitar as

live input? Or some other process?

I mean that when I start composing a live electronics piece, which

may involve any kind of instrumentation, I start to write basic ideas,

harmonies, and techniques on paper while creating the electronic part

too. The live electronics part that I create within AudioMulch involves

not just various contraptions and routing systems, but also complex

automation of various FX parameters. In that sense, besides the written

score, the mixing environment and the automation timeline become my

score. Just as how a composer writing a symphony would be aware of

every detail on the score, I also need to be aware of every detail

within the FX parameters and the automation timeline in AudioMulch.

With the help of this system, I can create sophisticated pieces in

which textures evolve spectrally over time.

Thanks Erdem!

Erdem has also kindly consented to answer a few questions from the community.

If you have any questions for Erdem click here to ask them in the Forum.

Reference

[1] Interview with Erdem Helvacioglu, Guitar Player Magazine, August 2007

original : http://www.audiomulch.com/articles/interview-with-erdem-helvacioglu